“Climate finance: who are the financiers and how to reach 1.3 trillion USD?”

From multilateral banks to climate funds and private investors, find out who is behind climate finance and how the world plans to mobilize USD 1.3 trillion to help developing countries fight climate change.

By Inez Mustafa | inez.mustafa@pesidencia.gov.br

"The trillion-dollar question is how and where to mobilize resources for climate finance," says Mikko Ollikainen, Head of the Adaptation Fund. Climate finance is a recurring theme in international climate negotiations, particularly at the Conferences of the Parties (COPs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Under the principle of "common but differentiated responsibilities," the Paris Agreement recognizes that developed countries should lead efforts and provide financial support to developing countries. However, Ollikainen warns that public sector resources are limited.

The need for climate finance was addressed by the Paris Agreement, which was adopted at COP21 in 2015. It is essential for supporting developing countries in implementing mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (preparing for the impacts of climate change) actions.

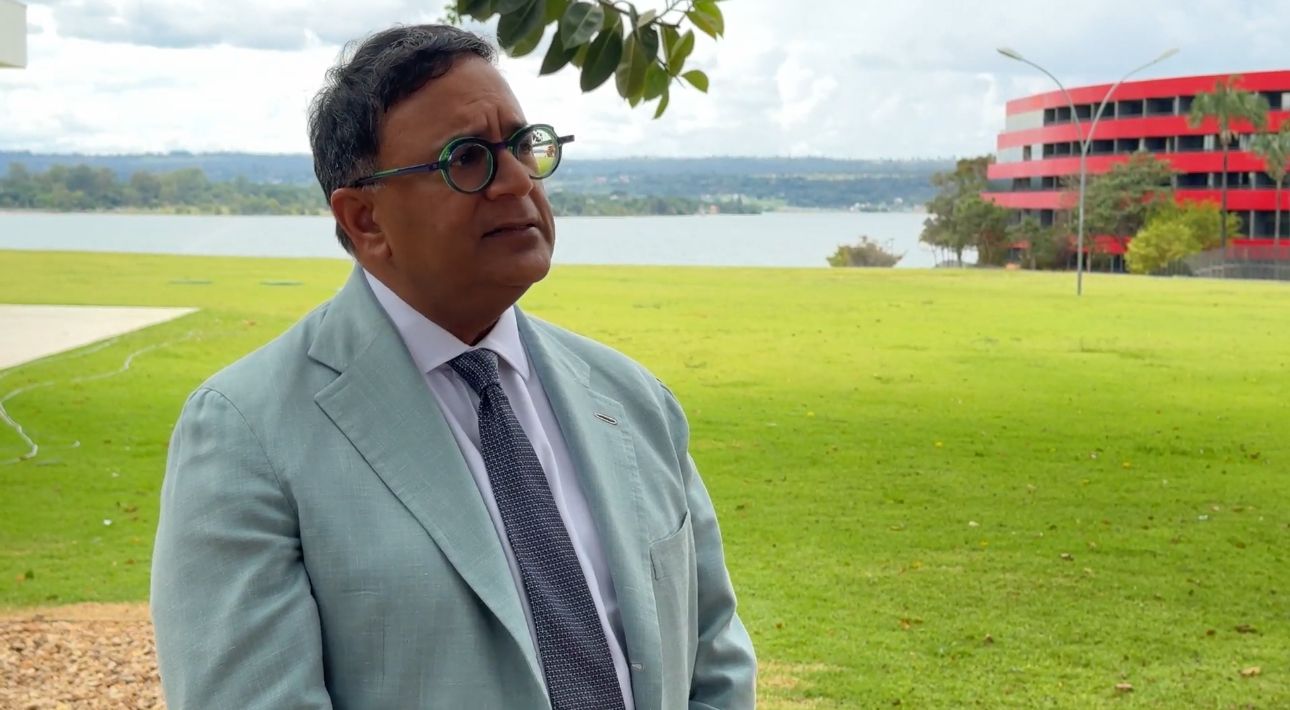

Before this agreement, in 2009, developed countries had already pledged to mobilize USD 100 billion a year by 2020 for climate finance —yet the promised funds never fully materialized, says Avinash Persaud, Special Advisor on Climate Change at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

Before this agreement, in 2009, developed countries had already pledged to mobilize USD 100 billion a year by 2020 for climate finance —yet the promised funds never fully materialized, says Avinash Persaud, Special Advisor on Climate Change at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

At COP29, nations agreed to provide at least USD 300 billion per year by 2035 for climate action in developing countries. The decision also calls on all stakeholders to work toward mobilizing USD 1.3 trillion in climate finance. Additionally, it stipulates that Azerbaijan and Brasil, as presidents of COP29 and COP30, will present a document in Belém outlining strategies to secure these funds.

"This amount is closer to what developing countries truly need," adds Richard Muyungi, Climate Envoy and Advisor to the President of Tanzania on Environment and Climate Change.

For example, Muyungi highlights that initiatives like the Great Green Wall—aimed at combating the Sahara desert’s expansion—rely on such funding to protect the African continent. "We need more financial support, innovative technologies, and the involvement of local communities for projects like this to be sustainable and effective," says Muyungi.

We need more financial support, innovative technologies, and the involvement of local communities for projects like this to be sustainable and effective," says Muyungi.

Multilateral Development Banks

"Nearly half of the climate finance flowing from developed countries to emerging economies comes from the system of multilateral development banks (MDBs), where developed countries are typically the main shareholders," said Avinash Persaud.

However, he adds, not all shareholders are developed nations, he adds. Countries like Brasil are major shareholders in MDBs such as the IDB, the World Bank, and the New Development Bank (BRICS Bank).

At COP29, MDBs pledged to provide USD 120 billion in climate finance to low- and middle-income countries by 2030, roughly double the 2022 amount. Persaud warns that this figure must triple to meet global needs. Achieving this, he says, will require greater capital investment from shareholders and government guarantees from donor nations.

Multilateral Climate Funds

Other key sources include multilateral climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, and Loss and Damage Fund. For Miko Ollikainen, "direct access to the funds allows countries to learn and develop their capacity to deal with climate change.

According to the head of the Adaptation Fund, "We need to develop these capacities not only at the federal level but also at the municipal level because we need to take these capacities to the communities, which have to learn to live with this situation that they didn't cause. He emphasizes the importance of supporting social groups that are directly affected by climate change so that they can develop their capacities in the long term.

Brasil's role in climate funds is significant, both as a recipient of resources and as a contributor. In the Global Environment Facility, in addition to being a financial contributor, Brasil has access to resources for projects related to biodiversity, desertification, and pollution. Since 2022, 26 projects have been approved in the country, with funding of USD 797 million.

Private Finance

Patricia Espinosa, former executive secretary of the UNFCCC, says it is necessary to diversify sources of finance and look at private resources.

"We must view the sustainability agenda as an agenda for competitiveness, for the well-being of people, for the well-being of society as a whole," adds the Mexican diplomat. She stresses that the private sector is one of the "drivers of the economy".

To attract more private capital, Espinosa suggests that governments need to promote national policies that provide tax incentives for the participation of private finance in climate adaptation and mitigation projects.

In addition, he says, it is important to involve communities in the process when thinking about projects that could be of interest to the private sector. "The cost of inaction must be taken into account, as this aspect is not yet fully integrated into risk assessment," Espinosa concludes.

English version: Trad. Bárbara Menezes